-

there are a number of field recordings of the Mbuti, Babenzele, and other pygmy tribes that you can listen to. they're very much field recordings, recorded as they go about their day-to-day lives, with all the tape hiss and insect noise that goes with it.

Originally Posted by BigDaddyLoveHandles

Originally Posted by BigDaddyLoveHandles

it's pretty remarkable music, very polyrhythmic and contrapuntal. the first field recordings done in the 60's were a big influence on Gyorgy Ligeti and Steve Reich. definitely worth seeking out.

-

03-03-2015 10:24 AM

-

As mentioned previously, the association of "sad" with minor chords is largely (if not entirely) culturally conditioned. It's not inherent in the pitches themselves.

Originally Posted by DaveWoods

Originally Posted by DaveWoods

But there is surely something objective about how our ears perceive interacting frequencies. The difference between a "simple" sound and a "complex" one must be due to physical content of the sound - the number of different frequencies or overtones, or their relationships to one another. (Any emotional associations would come later.)

It's worth remembering there is no music in nature. There may be individual sounds that could pass for musical tones - such as our own voices, the calls of certain animals, the wind in the trees. But there is no such thing in nature as an interval or a chord: an artificial construction consisting of two separate pitches. (It might just occur accidentally in nature, for a moment, but obviously devoid of any intention or meaning.)

Our hearing has naturally evolved to help us make sense of the sounds around us, especially to be able to identify sounds critical to survival. That's why our ears are so good with timbre. (Is that a friendly horse clearing its throat? Or a tiger growling?)

IMO, when we hear something artificial, like an interval or chord, our ears try to make sense of it (first of all) as a single sound - something produced by a single source. That means we expect the different frequencies we pick up to be overtones of a single note. At least, if our auditory system can line them up in that way, then we experience the sound as "single", "blended", or "stable". That would be the case when the individual frequencies have simple ratios with one another. It's most obvious in the octave, where the ratio is 2:1.

Most human cultures recognise "octave equivalence", which is simply the perception that those two notes are in fact "the same note" (ie, two overtones of the same note). If an octave is exactly in tune, and the notes are exactly simultaneous, it's very hard to tell that it is in fact two notes.

A perfect 5th is 3:2, and here we can usually tell two different notes are present, but again the blending is very strong. As with the octave, both notes could be overtones of a lower note (octave below the bottom one). They therefore belong together.

A perfect 4th would be the next simplest ratio, at 4:3. But here, the perception (assuming now, some musical awareness!) is that the top note is the natural root - ie it's really an inverted 5th. Eg. whichever way up the notes C and G are, C is always the root, because both notes belong to the harmonic series of C; and C is not part of the harmonic series of G (at least not until way up at the 19th harmonic...).

Next in the ratio list is 5:4, the major 3rd. We're growing a little more distant now from the "1" of the ratio that ties the notes together - but the natural root is still an octave of the lower note. (for C-E, the natural root, the fundamental of which both could be overtones, is 2 octaves below C.)

Next - back on topic! - is 6:5, the minor 3rd. The problem now is that the nearest fundamental pitch that both those notes could be overtones of is another note entirely. The notes A-C are overtones of F.

IOW, we could still (biologically) perceive A and C to be related, but more like cousins than brother or sister (or maybe uncle and niece rather than father and daughter ).

).

When it comes to a triad chord, we have three intervals to interpret (subconsciously of course). 1-3, 1-5, 3-5.

In the major triad, ratio 4:5:6, all of these tend to confirm the nominal root as the actual (acoustic) root. In an A major triad, all three notes could be overtones of an A two octaves below the root. Everything points (down) to A.

With a minor triad, things are not so straightforward:

A-E: root = A (very strong)

C-E: root = C (quite strong)

A-C: root = dunno? F??

So while the major triad is perceived as "simple", acoustically sturdy ("right"), the minor comes across as "complex". The nominal root seems clear(ish), but there's other stuff going on there....ambiguous... mysterious... and it's all down to that C note, of course.

That could easily explain how we've found it easy to accept the cultural associations of "happy" and "sad".

Our musical culture actually provides us with a very limited palette of sounds to draw from and make sense of. If we're offered those two choices of sound, and have to make an assessment of their meaning: "which is the sadder?" - we're going to go for the minor, undoubtedly.

If you can imagine a scenario where the only two chord choices were between minor and diminished, then we'd be forced to agree that diminished was sadder (much less acoustically stable), and therefore minor was our "happy" chord.

IOW, there's nothing inherently sad about minor. I.e., its sadness is "relative", not "absolute". In a field of very few candidates, if we want a "sad" sound, minor is probably the one we're going to vote for. (We pick diminished when we want something "seriously f***ed up" )

)

Lastly, let's not forget an easy way to make a minor key song sound happy: play it fast. (Tempo has way more impact on mood than key quality.)

(Tempo has way more impact on mood than key quality.)

Last edited by JonR; 03-03-2015 at 12:21 PM.

-

Not sure I buy the "no music in nature" item

What about birds singing to each other? I don't know this for a fact...but I bet there is some kind of musical thing going on....almost certainly "call and response" and probably something resembling counterpoint---which to some people might be disguised harmony...I bet whale mating calls could be transcribed and analyzed musically. I wonder if animals traveling in packs always howl in unison....what about female and male wolves? Course maybe the male wolves are off at some casino lounge, acting like lounge lizards, rather than proper hierarchically based carnivorous pack animals.

And then there was my gf's cat: When it got a little too familiar...I would pick up my guitar and play a nice tri-tone "power chord"----or a Hendrix c7+9---no more cat on the bed. It would then return when I would play something lyrical or a nice chord melody. (Didn't like Monk-ish kind of stuff, though...I guess he was a honky cat, and not a cool cat.)

And then there is the cry of the loon saying "Oh Hoagy Carmichael....bring me the rest of that Skylark song...it shows promise, young man....shows promise, young man..."

Seriously though, to say that all musical intervals...even ones outside of harmonic series are just culturally conditioned seems too strong a statement...probably there is a continuum going on here.

-

great info , well presented Jon

Originally Posted by JonR

Originally Posted by JonR

many thanks for clearing up the maths

for us

ps

whole tone scale sound kinda magical/

full of expectation to me

as used at the xmas panto etc

-

Well, it depends how you define "music" of course.

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

As humans, interested in non-essential artistic uses for natural phenomena, any natural sound can be drawn into the arena we label "music".

As humans, interested in non-essential artistic uses for natural phenomena, any natural sound can be drawn into the arena we label "music".

We can call the noises birds or whales make "songs", mainly because they employ identifiably pitched sounds. (I doubt we'd say lions sing to each other....) IOW, they resemble the noises we make that we call "songs".

But in the context of this thread I was deliberately using a narrow definition - narrowed even to European cultural parameters - to mean "intervals and chords using pitches drawn from a scale, and related - albeit debatably - to the harmonic series".

There may well be "music in nature". But birds don't sing intervals or chords, not in a deliberately chosen way anyway. In any case, this is all about the way we perceive sounds. We have no idea how birds perceive their own sounds, and we don't need to know.

Having said that, the way our brains work is to look for patterns. We're compulsive pattern seekers. We know patterns usually mean something, and might be important, but we love them so much we see them where there aren't any (or where they have no meaning), and in the last resort we'll make our own. And of course this applies to patterns in sound (and in time) as well as visual ones.

Eg, we might hear a bird call (cuckoo?) that sounds "musical", because those two pitches are heard (subconsciously) to have a simple frequency ratio. "hmm, those two pitches are related". So they sound good - they make a pattern, maybe they have a meaning or, if they don't, we can give them one!

IOW, the love for pattern that allows us to create what we call "music" will also lead us to label some natural sounds as "music" if they have similar superficial qualities. I wouldn't deny that.

But "call and response" is a linguistic, communicative practice, that becomes adopted by music. IOW, it's one of the ways in which music makes itself understandable, by mimicking certain verbal practices. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

If I were to yell out your name in the street, and you responded by saying "oh hi, how are you?", that's "call-and-response", but is it music?

Well, now you're really stretching it. If there is any bird or animal behaviour that could sensibly be described as "counterpoint", I'd love to hear it. (NB: it has to follow counterpoint rules, it can't just be "two notes at the same time". Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

)

)

Another stretch of definition. And adding "disguised" doesn't really help your case. (If it doesn't sound like harmony, is that because it's disguised? Or, er, because actually it isn't harmony at all? Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

How could we possibly tell?)

How could we possibly tell?)

I think you'd lose your bet - unless you're using the word "analyzed" very loosely. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

"Analyzed" according to what principles? It wouldn't be enough to identify frequencies - assuming they held notes (without bending or swooping) for long enough. That's not analysis. And if two whales happen to make sounds simultaneously that we can identify as a musical interval - which is certainly possible - how do we know if that's intentional?

And if we can guess that it is (eg by examining hours of recording and finding recurring patterns with no other explanation) - or even if we don't care whether it is or not - what principles do we base our "analysis" on? Major and minor keys?? Chord progression?? Species counterpoint? (nice "species" pun... )

)

I'm sure they often do, but does that make it "music"? Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Now you're talking... Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Yup, there are plenty of pet owners who like to assign musical awareness to their animals: dogs or cats often howl along when master/mistress attempts to play their instrument. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

It's definitely as if the animals sense the human is making some kind of meaningful but mysterious call.. "hmm," the beasts think, "this is not just that strange mumbling noise these humans make to each other all the time with their mouths, this is something else ... But what the hell is it? Should I be scared? Are they dying? Are they calling their pack? Are they on heat? Are they in pain, or hungry? Don't worry master, I'm here, I'm here! Hooowwwwlll!!! (actually if you're just on heat, forget it, man...)"

The cultural conditioning is the emotional associations. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

I.e., it can easily be argued that - while "intervals" are artificially created - they are chosen because they derive from the natural law of the harmonic series (the only physical basis for musical pitch and harmony). I.e., they are "natural" in that sense. They then get used in certain ways in music, which leads to various emotional associations and meanings. So the meaning we ascribe to (say) a minor 3rd is not "natural" in an absolute way. It's a result of all the music we've heard, and the meanings we've learned to link with that music.

It's rather like we can mix up a blue pigment for use in a painting, and say it's a "natural" colour because the sky is that colour, or because the substance we're making it from has a blue colour in nature. We are synthesising something, but in a direct line from nature.

But how we use it in a painting - and the emotional association we make with that colour - is something that is culturally conditioned, via the choices artists have made in the past. Does "blue" mean "calm", "peace", or "distance"? Or "depressed"? or "pornographic"? Cultural context tells us that (and maybe other things). The colour itself is devoid of inherent meaning.

Cultural context tells us that (and maybe other things). The colour itself is devoid of inherent meaning.

-

Go read the wikipedia entry on "Bird vocalization". You will learn a lot ( I did), e.g.:

1. bird calls are frequently communicative---they vary with the context, and can announce alarm, danger, the possibility of a food source, or other matters

2. bird calls are learned---and there is extensive research on what happens to birds deprived of their ability to learn

3. students of bird song distinguish between "bird songs" and "bird calls". In fact that article states "Many birds engage in duet calls." This is sometimes referred to as "antiphonal" response

There is a discussion back and forth in that article re: whether bird song is "musical". The article cites one authority, and that states that another has "refuted it" by stating that "[B]irds are ...filtering out and reinforcing the available set of overtones from the fundamental tones of their vocal chords..." To my mind, this does not refute the claim, but rather supports it.

There is no need for humans to "assign meaning" to bird songs---the birds themselves have supplied the meaning---e.g. food source, "come get me---I'm good mating stock", "Danger!", etc. If this is not "deliberate chosen behavior"---then I don't know what else to call it: It is not instinct---cf. point #2 above, but learned and deployed. (not too different than learning a bebop lick, and playing it which says "I've listened to bop...understand it...respect it...and am showing you that I can play it too.")

I'm no naïve anthropomorphist when it comes to animal behavior. For the record, I think cats are highly instinctual, highly habitual creatures who are not too terribly bright, as evidenced by their willingness to repeat non-adaptive behavior (tree climbing; meowing to go outside in freezing cold weather-repeatedly--on consecutive days or weeks at a time when they would do so, and then meow to come back inside after they'd figured out, it was still cold.) But cats only meow to humans by and large. While I think them not too bright, they do have an ability to communicate. Interestingly, lions are virtually the only pack animals in the cat family. Their social interaction is much more highly developed than say tigers, or a lynx, etc. which are pretty much "lone wolf" hunters. As such, their communication with each other is almost certainly more highly developed.

To sum up---intentional behavior in producing sounds, derived from harmonic overtones found in nature , to achieve a social goal...sounds a lot like what we call "musical" activity. (Course they don't sight read, or study counterpoint theory--but again that raises an interesting point. I've read that Bach thought all music sacred, in a sense, as it showed evidence of God's majesty in creation (or as found in nature, i.e. the harmonic series, if you don't want to be deist-oriented). I think he probably thought he wasn't discovering rules of counterpoint--but simply applying them. While not a student of classical 4-parts writing, I am also told he frequently breaks the rules....and my guess is that he did so, because it sounded good. To me, the greatest musicians are humble individuals---because music is too vast to be "boxed in" by human rules or limitations... nobody ever really masters music---because that is an impossibility. At any rate, that is how I see it.

-

Now I slam my computer when I see more posts in this thread -- is that cultural conditioning?

-

Come on guys. Put a Lydian on it.

-

I once heard a guitarist who had worked out the nearest notes to every phrase of a Snoop Dog rap. When he played alongside the rap vocal track, Snoop Dog's rap suddenly became "music" to my non-rap-fan ears. It was cool and a bit of a paradigm shift.

-

Just talking about static chords here:

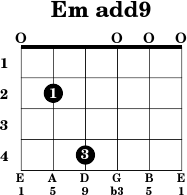

The Maj7 chord with a flat 5 can sound kind of sad in a floaty kind of way; and the minor 7th chord doesn't sound too sad; maybe nostalgic and introspective but not sad. In fact, speaking of minor, the whole Dorian mode sounds kind of bright to my ear; not as melancholic as Aeolian. The saddest chord of all though is the minor add 9; especially this voicing:

Last edited by wildschwein; 03-05-2015 at 07:11 AM.

-

Yup. As illustrated perfectly - deliberately and overtly - in this pop classic:

Originally Posted by wildschwein

Originally Posted by wildschwein

0:36, and behind the title phrase in the verses (1:15, 2:32, etc).

The Police also used min(add9) chords - along with all the other add9 chords - in the stalker's anthem "Every Breath You Take".

Adding 9ths is a standard device for "poignancy", and putting them on minors adds intensity. Arpeggiating the damn things mechanically then adds obsession to depression... (clever songwriting!)

(clever songwriting!)

Last edited by JonR; 03-05-2015 at 10:58 AM.

-

Sure. What's that got to do with music?

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Well, it still comes back to how we define "music". Any of us can define it how we like, really. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

I'm not saying birdsong doesn't sound "musical" to me, in a broad sense. It's pretty, it has varied pitches, it sometimes has rhythmic repetition.

But in another important sense, it's nothing like music. Where is the form, the structure, the intervals, harmony? (I mean obviously I'm applying very restrictive human parameters to it, but that's kind of the point.)

I'm sure there are some birds who develop their songs in ways very like human music, even with little apparent practical survival value.

From the other perspective, some have explained human music as just a fancy way of attracting mates, same as in birds. (A strong singing voice is not a bad indication of good health, at least; and inventiveness suggests intelligence.)

(A strong singing voice is not a bad indication of good health, at least; and inventiveness suggests intelligence.)

I like the hypothesis that music predates language, and began as human calling, exactly equivalent to animal calls, used for any purpose for which humans might have needed to make noises. Verbal language developed later.

Hence the sense that music is universal (between humans), and also the sense that it communicates something, although we can't define what exactly (its meaning is untranslatable), and also that it's mysteriously deep and important.

Now that we have verbal language, music has been relegated to an artform, games with sound, in the same way that sport has (some of the time anyway! ) replaced violent conflict.

) replaced violent conflict.

Agreed. It sounds a lot like it. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

But still, it's deviating somewhat from the point I was (maybe not very well) arguing, which was about all the aspects of human music which are not found in birdsong, in particular harmony and its associated meanings. (Harmony itself is a uniquely European invention only a few centuries old. In terms of the millennia of human music-making it's a bizarre blip.)

The Greeks believed in the "harmony of the spheres" too, that the movements of planets were musical in some way. But then they saw few of the distinctions between art, religion, philosophy and science that we like to draw. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Yes, but that would be a natural outcome of his belief. If you believe in God, then he's created everything, including the rules we like to use to make music. (He made us in his image after all...) It's a self-fulfilling thing. If it sounds good, it must be right. The better it sounds, the more sacred it must be. How could it be otherwise? Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Meanwhile, a scientist would point to the human love of patterns, a result of the brain's evolution into a thinking machine. Spotting patterns (of various kinds) is important for survival, and for dominance. That's why we love them, and look for them everywhere - to the point of obsession sometimes. Human art of all kinds is about playing with patterns.

I agree. Originally Posted by goldenwave77

Originally Posted by goldenwave77

The rules in the books come later, as a way of trying to understand (and reproduce and learn from) what past musicians have done. They're not laws one has to follow - unless one really is trying to mimic vintage music exactly. The only forms of music that one can create using a rule book is music that is already dead. You can't write the rule book for music that is still living and developing.

Music theory doesn't say "this is how you must do it"; it says "this is how they did it". And the word is "how", not "why". The "why" (like you say) - for any composer or musician of any period - is "because it sounds good".Last edited by JonR; 03-05-2015 at 11:41 AM.

-

Originally Posted by EightString

Originally Posted by EightString

OK, you win. This was my last post.

-

Okay, what does this chord sound like to you: Maj7(add b6):

CMaj7(add b6): x36453

To me, it sounds like Raymond Burr's eyebrows in Perry Mason. Amirite?!

-

Nice examples. Always loved that Yardbirds tune. Gregorian monastery pop.

Originally Posted by JonR

Originally Posted by JonR

-

Adding a 9th to a minor chord creates a major 7th interval between the 9th and the b3 in the chord.

Example E G B F#, G and F# form a major 7th interval which is dissonant. Also, the perfect 5th overtone generated by B, is F#. A minor triad with an added 9th is a powerfully compelling chord.

-

Yep, the A minor with the added 9, especially in the open position, is a very moving and mysterious chord. I remember learning it as kid from an Ozzy Osbourne song in which Randy Rhoads was the guitarist. The actual song escapes me at present (maybe "Believer" off Diary of a Madman)--it was in one of the quieter passages of the tune. I learned a lot of theory from RR.

Originally Posted by DaveWoods

Originally Posted by DaveWoods

Last edited by wildschwein; 03-06-2015 at 10:20 AM.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

No Lick November

Today, 12:28 PM in Improvisation